Being average, by design, vs Being better than average

Understanding NPP and Its "One-Size-Fits-All" Design

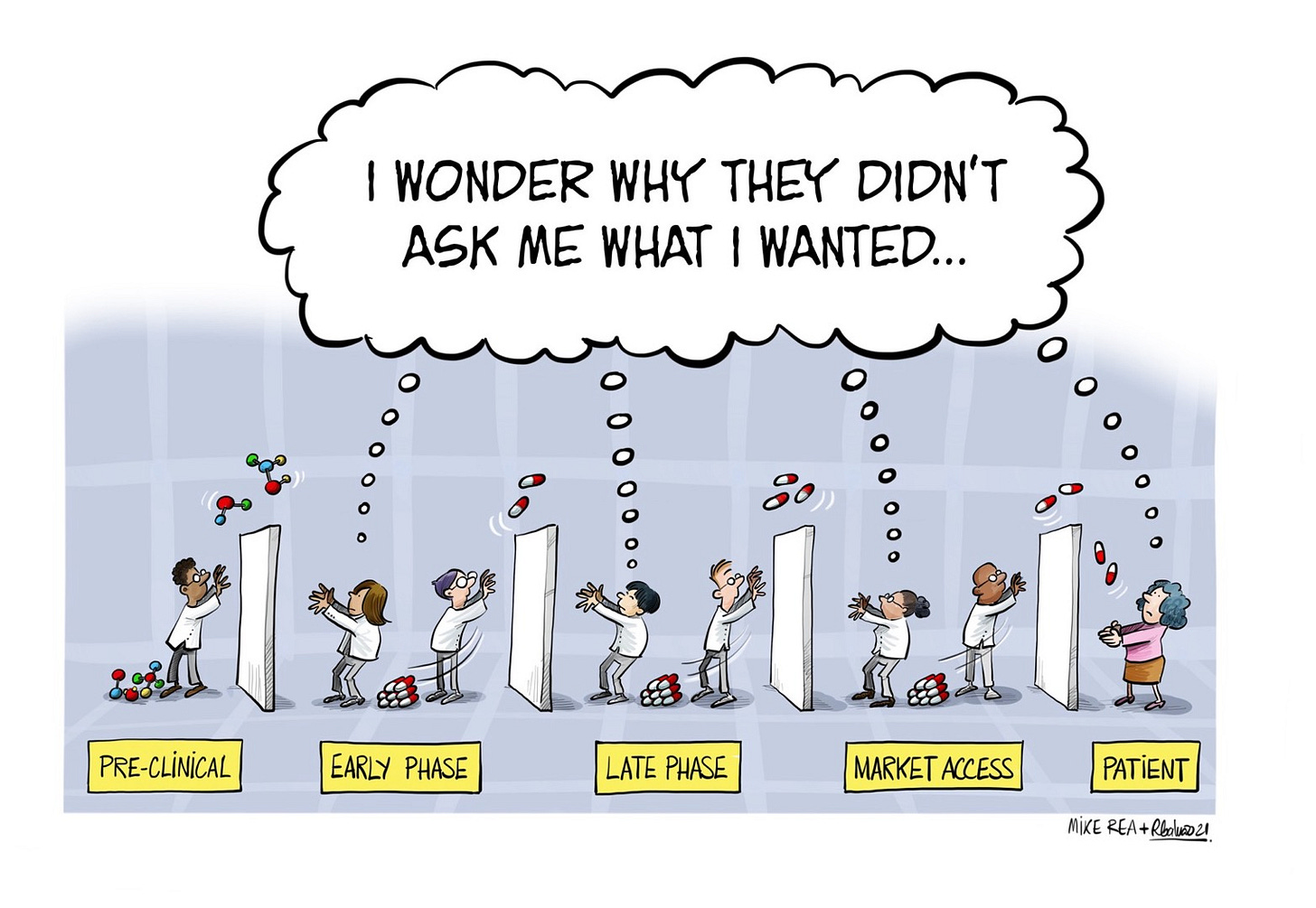

New Product Planning (NPP, often used interchangeably with New Product Development or NPD in broader business contexts) is the systematic process of ideating, validating, developing, and launching new products.

In industries like ours, it's a dedicated function that intends to integrate commercial ‘insights’ into R&D pipelines to ensure market viability. More generally, it encompasses stages like idea generation, concept testing, prototyping, market analysis, and commercialization. Companies implement NPP variably, so it is hard to be specific about what it has achieved, or what it hasn’t, but I’ll address the core of what it could achieve if it tried to…

Let’s focus: most of what NPP produces goes nowhere. In pharma and biotech, the attrition rate is staggering - only about 10% of drug candidates that enter clinical trials ultimately gain approval, with failure rates reaching 90% overall due to issues like lack of efficacy or toxicity that rigid processes fail to address early. Our industry launches very little of what is NPP’ed, and a small proportion of what becomes a launched new product ever becomes commercially successful - think of the billions poured into R&D pipelines where high attrition in late stages (e.g., 70% failure in Phase II for oncology drugs) wipes out potential breakthroughs.

The hallmark of traditional NPP is frameworks like the Stage-Gate model, popularized by Robert G. Cooper, which breaks the process into sequential phases separated by decision "gates" where projects are evaluated, funded, or killed. By design, this standardization treats every product similarly: the same checklists, milestones, and risk assessments apply regardless of the product's novelty, market dynamics, or competitive landscape. In biotech, this might mean applying identical evaluation criteria to a small-molecule drug for a common disease as to a gene therapy for a rare orphan condition, ignoring the vastly different regulatory paths, patient populations, or innovation risks. It's like using a single recipe for every meal - efficient for mass production but unlikely to produce gourmet results. Or, in pharma terms, it's akin to prescribing a standard antibiotic regimen to every patient with an infection, regardless of bacterial strain, patient genetics, or resistance patterns - safe and predictable, but rarely optimal and often leading to suboptimal outcomes. This uniformity ensures predictability and minimizes outright failures (e.g., culling weak ideas early), but it also caps potential upside by discouraging deviation. The result? Average outcomes, where products meet basic market needs but rarely dominate or disrupt.

Why NPP Inevitably Leads to Average Outcomes

The core issue is that NPP's rigidity optimizes for the middle of the bell curve. Here's how it plays out:

Risk-Aversion Kills Bold Ideas: Gates prioritise low-risk, incremental improvements over radical innovations. High-uncertainty projects - those with the potential for outsized returns - often get axed early because they don't fit neat evaluation criteria like proven market demand or quick ROI. This favors "safe" extensions of existing products, leading to commoditized offerings that blend into the market rather than standing out. For instance, in consumer goods, this might mean tweaking a detergent formula instead of rethinking sustainable packaging from scratch. In pharma, consider Spebrutinib, a BTK inhibitor that failed in early clinical trials despite high specificity; its low tissue exposure/ selectivity didn't align with standard potency-focused gates, requiring toxic high doses that killed the project prematurely. Similarly, many biotech firms shelve novel modalities like CRISPR-based therapies early if they don't show immediate "proven" paths, missing out on transformative potential while sticking to me-too drugs.

Sequential Rigidity Slows Adaptation: Traditional NPP is linear, like a relay race: one phase hands off to the next. In fast-moving markets, this delays feedback loops and makes it hard to pivot based on real-time insights. By the time a product launches, it might address yesterday's problems, resulting in mediocre performance against agile competitors.

Data backs this: Up to 80% of product launches fail or underperform, often due to mismatched market fit from inflexible planning. In pharma, that can be 95-98%, with rigid Phase I-to-III sequences preventing mid-trial adjustments. For example, Remdesivir's development for COVID-19 highlighted this - despite strong in vitro data, its clinical efficacy was limited by poor lung exposure versus kidney toxicity, issues that a more adaptive process might have flagged and iterated on earlier, rather than locking into a fixed protocol. It's like running a lab experiment with a predefined protocol that can't be tweaked based on interim results, leading to wasted resources and average (or failed) compounds.

Homogenization Across Products: Since the process doesn't customize for unique contexts (e.g., a tech gadget vs. a biotech drug), it enforces average benchmarks. Teams focus on hitting universal metrics like cost targets or regulatory compliance, sidelining creative differentiation. This "averaging" effect is evident in typical critiques where NPP can be called burdensome and constricting, leading to scope creep or ambiguous requirements that dilute originality.

In biotech, this means treating all candidates the same - small molecules, biologics, or cell therapies - under one umbrella, ignoring modality-specific risks. Aprepitant, successful for nausea but a failure in depression trials, suffered from rigid designs not tailored to psychiatric nuances, resulting in inefficacy despite the drug's potential. It's analogous to using the same clinical trial template for every indication, averaging out the unique biology and patient needs, which contributes to high attrition rates like 59% in Phase III for oncology.

Real-world example: Famously, Kodak's adherence to rigid NPP processes in the film era blinded it to digital photography's potential. The company had the tech but treated it like any other incremental project, leading to average (and eventually obsolete) outcomes while disruptors like Canon surged ahead. In pharma, Merck's experience with Vioxx echoes this - rigid adherence to cardiovascular safety gates post-approval led to withdrawal after massive investment, while more flexible processes might have pivoted earlier. Or consider the industry's slow shift to biologics in the 2000s; companies stuck in small-molecule NPP missed the boat, yielding average portfolios as innovators like Genentech dominated with targeted therapies. In essence, if your goal is to outperform - say, achieving 2x market share or viral adoption - NPP can be counterproductive. It's engineered for survival, not supremacy, in a world where averages get commoditized.

If Not NPP, Then What?

Alternatives for Outperformance

To break free from average, shift to flexible, tailored approaches that treat products as unique opportunities. These aren't abandon-all-process chaos; they're evolutions that prioritize speed, iteration, and customization:

Agile Product Development: Borrowed from software, this emphasizes iterative sprints, cross-functional teams, and continuous customer feedback. Unlike Stage-Gate's gates, Agile allows overlapping phases and rapid pivots, ideal for innovative products in uncertain markets. Example: Spotify uses Agile to roll out features weekly, outpacing traditional media players stuck in yearly cycles. In pharma, a leading company (per McK, so take their word for it…) doubled its R&D capacity in one year without adding resources by devolving 80% of decisions to teams and extending agile to over 700 scientists, accelerating development times and fostering innovation in trial designs.

Hybrid Models (Agile + Gates): For teams wary of full Agile, combine lightweight gates with iterative loops. This culls truly bad ideas while allowing flexibility for breakthroughs. BMW adopted a hybrid for electric vehicles, accelerating development and capturing EV market leadership early, although it clearly lost this lead as soon as a true disruptor entered the market. In biotech, Pfizer's "Dare to Try" program blends agile experimentation with gated reviews, building a culture of flexibility that has sped up vaccine and therapy pipelines, like in their rapid COVID-19 response.

Lean Startup Methodology: Focus on building minimum viable products (MVPs), testing assumptions quickly, and scaling only what works. This customizes the process per product, avoiding the "all products equal" trap. Airbnb's early MVP (a simple website for air mattresses) bypassed traditional planning, leading to explosive growth. In pharma, a global company reduced brand strategy creation from over two years to 90 days using lean MVPs and cross-functional teams, minimizing silos and aligning with market needs faster.

Bounding Box or Rugby Approaches: Set high-level boundaries (e.g., budget, timeline) but let teams self-organize within them, encouraging holistic collaboration over sequential handoffs. Honda used this "rugby" style in the 1980s to develop cars faster than competitors' relay-like processes. Pharma has recently embraced a ‘scrum’ approach, although this often seems more like play than real work - yet successes like a large pharma's SAFe implementation show it works, improving team efficiency and project delivery across 80+ members after a year-long transformation.

Our FIVE-X approach: If you start with the truth that it’s impossible to know where the overlap between what your product is great at (which is unknown in early phase) and what the market wants (hard to know when you’re 10 years from market), you approach things differently. Early phase becomes exploratory, instead of confirmation-biased - phase I is less about just checking your product is safe enough to proceed to a simple phase II, but more about using the time to understand what the different market opportunities might be. It's like mapping a genome: instead of assuming one gene variant, you sequence multiple possibilities to find the best fit. Phase II, instead of just providing proof of (simple, low technical risk) concept, tests a range of potential concepts, each of which might have different value to your Target Value Profile or Target Opportunity Profile - analogous to running parallel experiments in a lab to hedge against uncertainty. This inevitably means that you start a Phase III with a lot more confidence in the chosen path - when you have only one option, you have no choice, but with FIVE-X, you're selecting from validated branches, reducing the 90% failure risk, and increasing the chance to see, and hit, a real opportunity.

These alternatives demand more upfront customization - assessing each product's risk profile, market speed, and innovation type - but they yield superior results by amplifying uniqueness rather than averaging it out.

In pharma, where rigid NPP has led to only 17 FDA approvals in low years despite billions in R&D, these methods offer a path to true disruption.