Evidence of the absence of evidence

‘Attrition’ is a word that typically applies to drop outs, or wearing away. In pharma, it is used to mean the opposite of ‘success’ in clinical studies: a drug that is worn away by our process is part of our expensive inevitable R&D attrition.

It is entirely possible that good drugs are lost to bad process, to being put into the wrong studies, the wrong proofs of principle, the wrong proofs of concept, the wrong market. Although it is uncomfortable to admit, few would argue that this could not possibly happen.

It would be impossible to argue that our process must, by design, capture all of the opportunity in the molecules that went into the pipeline as fresh candidates. Our bright eyed hopefuls all set off on the road to patients and then hit two things: decision making and science. From that point on, the decisions chose the science they’d hit.

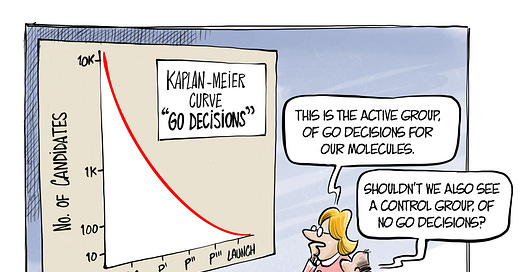

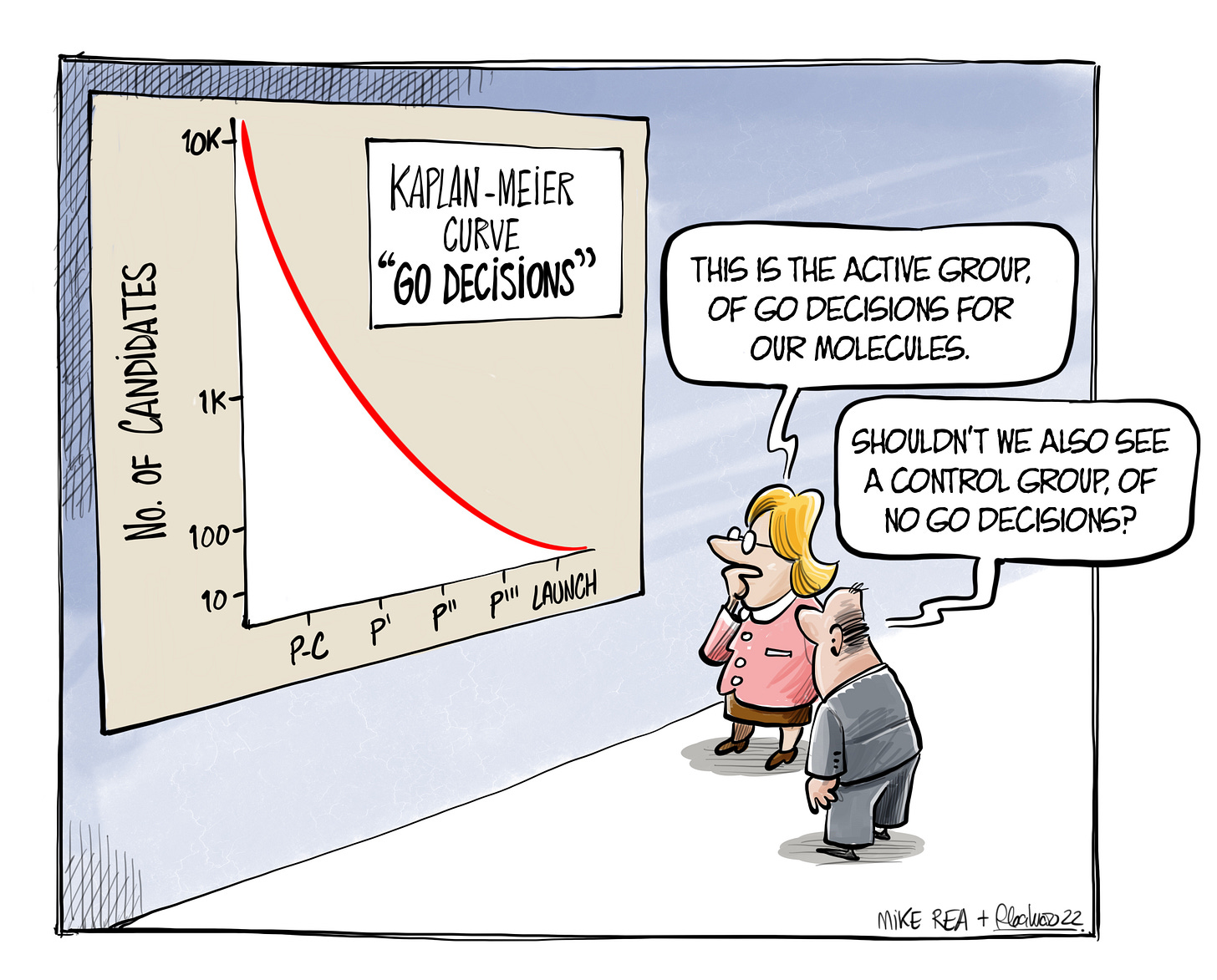

All of the data we have on what happens from that point on is essentially the active treatment arm of a massive study. Pharma (says it) doesn’t like making decisions in the absence of evidence, but the evidence that is gained from the early part of the journey is the result of prior decision making (prediction, generation of hypotheses, forecasting, etc.). So, in this active treatment arm, pharma makes decisions based on evidence of absence (safety signals) or evidence of presence (a signal to continue, a market forecast pulled from thin air and market ‘research’). All the while, the absence of evidence to change course piles up to the side, like a massive snow bank (as I wrote about in Opportunity Cost/ The Cost of Opportunity).

We do know, from the lucky escapees of this process, that success often comes from this active treatment process being slightly loose around some edges. The great stories of serendipity are ones where the process didn’t work, and a glimpse was given into the control arm of ‘no go’ decisions - the alternative universe where we chose a different path for our candidates. But, what if that world has something to teach the old world?

It will remain odd, therefore, that an industry which is an evidence industry, a scientific industry, a data industry, looks mostly for improvements to a failing Development process; a process which has its roots in management consultancy, not in evolutionary success between competing models. Enhancements are sought to do the wrong thing slightly faster, to gain the wrong insight with slightly better confidence.

The opportunity in opportunity seeking is not just to bend the Kaplan-Meier curve in its midsection (the ‘quality of life’ separation), to keep drugs alive in their early years. It is to create more ‘overall survival’ - more great medicines getting to patients, because they were treated properly on their way. Addressing the absence of evidence problem is something we admire in Sherlock Holmes, in our physicians’ differential diagnosis, in military strategy. So it seems reasonable to admire it in ourselves.