Knowns, unknowns, knowables, unknowables

Most parents will recall the interesting journey they take with their kids - wondering what they'll be good at, what they'll be interested in, and hoping those two things coincide. And the anxiety that swirls about giving them an environment in which to develop those interests and gain signals about later-developing capabilities. Does the fact that Johnny can play guitar at 3 mean he's another Hendrix in the making or is it predictive of future mathematics ability? All of these anxiety is matched with wondering what might be good in future? Doctor or lawyer is a familiar refrain, but those 'safe bets' may be anything but - what if Blake can't make the good schools, or if Blake would actually hate life in medical or law school? Or, if, having made it, the discovery that being an average doctor in 2030 means Dr Google makes the role fairly functional.

Were you to hothouse Johnny as a guitarist, of course, you may well find that at 16 he's merely average. He may miss application, or the imagination to be creative instead of just playing what's in front of him. Or, even if he is still great, will that sustain? A study that showed how few players in the England Under 21 soccer squad go on to play in the England side was illuminating - one might imagine that if anything was predictive of your ability at age 25, it would be your ability at age 21... But it doesn't work that way.

You'll have no idea whether or not he might have been a good scientist, engineer or accountant. Then, consider the kids who are making fortunes from YouTube, or online gaming, or whose medical degrees became useful only when they pivoted to biotech...

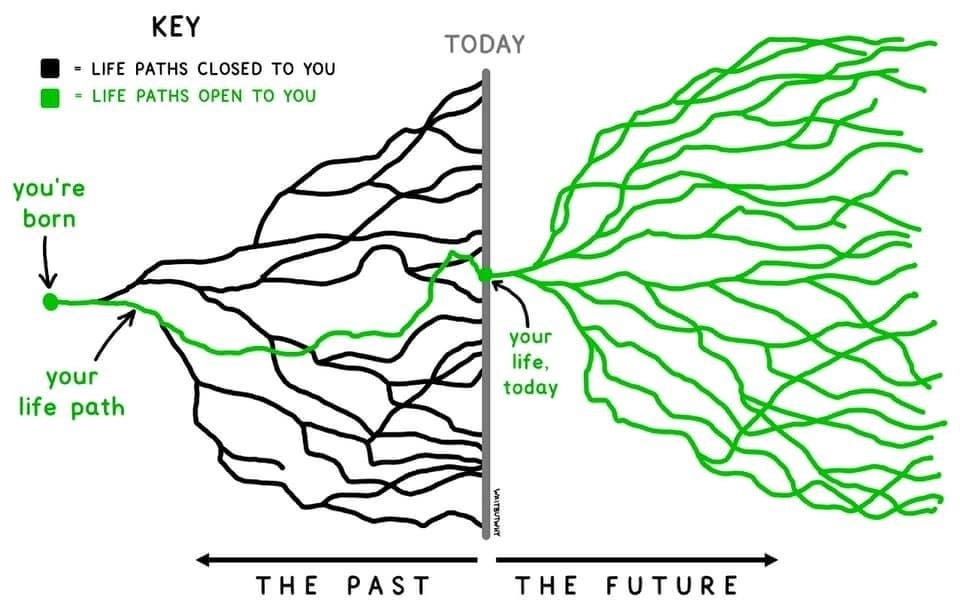

We often have the luxury of choice, but we're not far removed from the equity and equality conversation, where not all paths are available to all children, for a variety of reasons. This diagram, from the wonderful Wait But Why blog, illustrates this neatly - hopefully there are more life paths available to pursue in future than there were historically.

So, let's think about pharma. The harsh reality is that the past, as represented here, is the way drugs currently move through their potential paths. A decision to explore one Proof of Principle study, and not two, to conduct one Proof of Concept, and not two, will produce the left diagram by design. So, it places a lot of emphasis on your certainty that what the world needs next is a swimmer, or a mathematician.

If, like the rest of us, you wonder what the world will want of your children in 10 years time, welcome to the world of pharma as it should be. What skills will be essential, and which will be redundant? What to pick up now for hope that they're useful later?

But, I hear you argue, we know what the world needs our drugs to do... So, here is a fraction of the things that you do not know:

what the regulatory pathway will be when you get there

what the competitor set will be

how your drug will work in every subset of every disease you might work in

how many patients there are who have your disease

whether the effect you have in mice will translate even into a measurable effect in humans

You don't just know that you don't know these things. You know that some of them are unknowable... They're contingent, variable and potentially the kind of thing you could never know unless you built it: a regulatory pathway that you believe in, and that the regulator will say yes to, but only if you show it to them, and do the validation in phase II.

Most pharma process is built on ignoring this uncertainty. If you pretend it doesn't exist, who will ever know? Rejecting that pretence is at the core of Asymmetric Learning - the idea that learning faster and with more breadth is your competitive advantage - keeping open more paths until you can arrive at the ideal match between what your drug is good at, and what the world wants. Recognising that you may not be able to know that until far beyond Phase I, but that actions you take now will close or open some of your choices, should already be changing the way you do portfolio management.