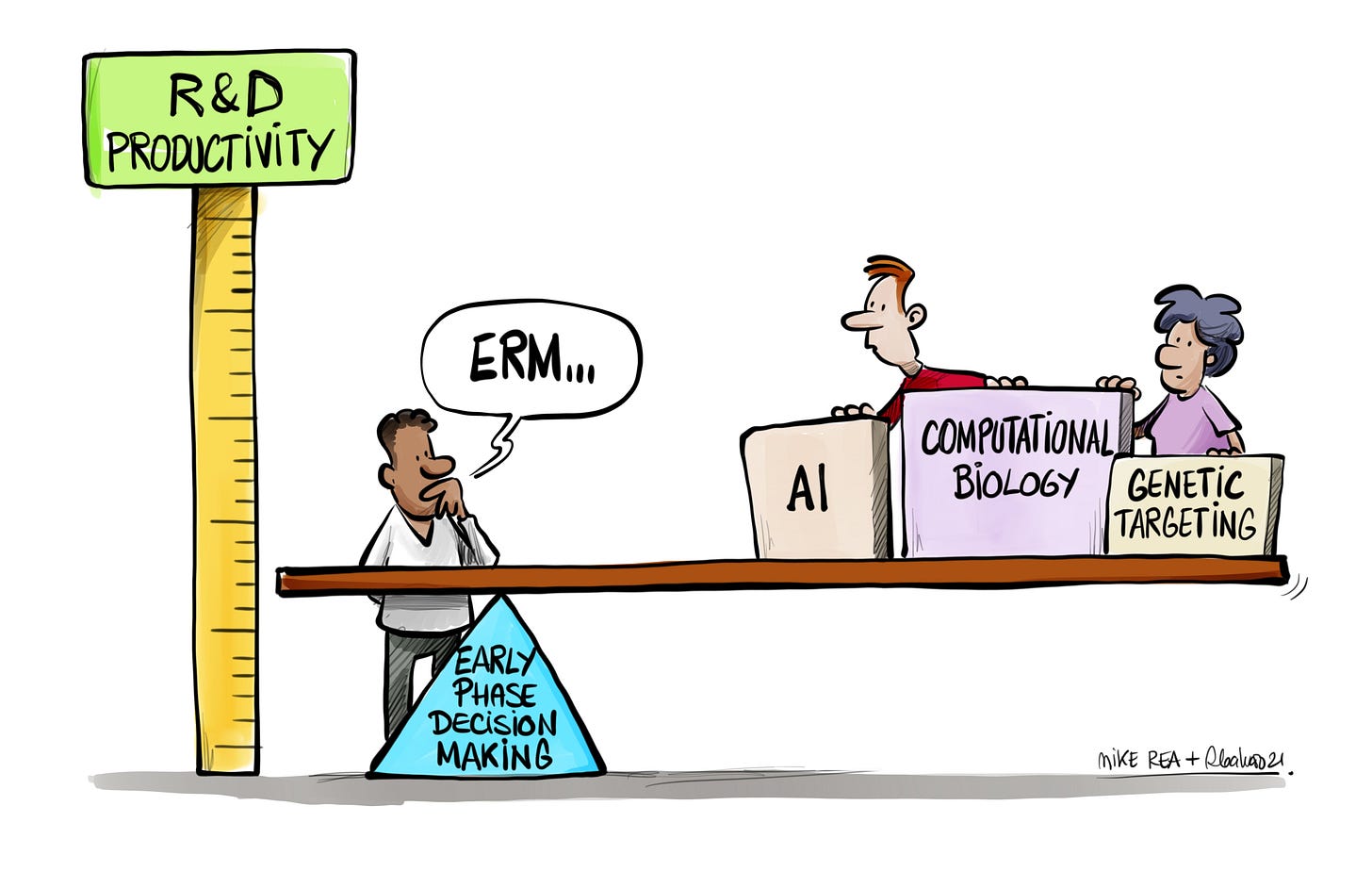

Moving the needle: moving the fulcrum

Improving R&D Productivity by improving decision-making in early phase

There are those who think the hard work is done by the time that a drug enters a pipeline - make a better drug in Discovery, and it is plain sailing from that point: it will speed through Development, with its destination and opportunity fully receptive. That belief is based on the possibility of designing better molecules for our pipelines - Development is simply a set of stepping stones that are predictably easy.

Certainly it is an enticing prospect, and one that has been sufficient to attract a huge investment in AI, computational biology, and more, to design 'better drugs'. But, as the adage goes, pharma's problem is not starvation, but indigestion. Good drugs stall in pipelines, or even at the starting gate, constantly. But that is not because of the limited understanding of disease biology (which is very limited, if we're honest), or the ability to design those molecules, but because early phase decision making, in many companies, is still based on an outdated model: that Development is linear, and confirmatory.

Development cannot be linear: the destination has to inform the journey, and it is impossible to make that decision before development starts. Many will suggest that the destination is a relatively simple exercise: 'this is an RA drug, and therefore...' But, that ignores the reality of positioning a drug in a marketplace at some point in the future: competitive differentiation, value proposition, and more, all of which need patient segmentation, competitive simulation, and predictions of effect size, markers of effect and more.

If you believe this is an RA drug, one that cures rather than treats, and therefore the course is obvious, your journey issimply confirmatory: your decisions will always be 'go or no go?'. Improve your starting set, and your output set has to get better.

But you cannot make that prediction. No matter how elegant your drug design, the hard reality of Development will mean that you have to test your design in the real disease, and in real people. Real disease is complicated, and that complexity is badly tracked into any system that could help design your molecule.

Instead, a better decision process is needed. That process needs to start with a view that early phase should be exploratory, instead of confirmatory - that there are things to learn, rather than just things to demonstrate. A confirmatory, linear Development doesn't need a focus on Decision Quality - decisions are relatively binary: do we have enough to proceed or not? All of your decision risk sat back at the point the product was assigned its TPP - hence the 1-2% success rates that we see across the phases, and across all major companies. However, confirmatory, linear Development is a significant reason for the decline in R&D Productivity, year on year. Improve your success rate, even by 100%, in that model, and your lever moves only 1-2%. Your $500 million AI Discovery deal looks the same to a Development process as a molecule found in a rain forest, or by hunch. Decisions taken early in Development do matter.

Strategy is the discipline of making better decisions.

Think about information that you need to collect: not just 'does this molecule work in this disease?' but 'will someone approve it, with the balance of effect and side effects that it will produce?', 'will someone pay for it?', 'will someone write a prescription for it?', 'who else will be on market when we get there, providing direct or indirect competition?', 'will patients take it as instructed...?' and hundreds of other variables. Each of those pieces of information is a key variable for your future success, and all inter-dependent. Vary one of those parameters and most of the others change. That is awkward in a linear, confirmatory process, so they tend to stick to extreme simplicity. Complexity, however, is a key design parameter in a better decision process - one that aims to manage uncertainty, rather than ignore it.

If it was possible to predict performance in real people in real studies, we wouldn't have to do those studies. But it is not, and we do. And what we find in those studies is often surprising. Those surprises are almost overwhelmingly interesting, and so many of our great drugs have pivoted constantly, in light of what has been observed. To observe and pivot means a study set up to observe more than one thing, and the ability to pivot means being aware that other destinations could be interesting, or valuable. Knowing that other destinations could be interesting can be done one by one ('this doesn't seem like it is going to do what we thought, but it does seem interesting in patients with lupus - is there an opportunity there?', or planning destinations back into the Development process, to inform an Exploratory phase.

As soon as you move the fulcrum of better decisions back into early phase, the opportunity of better path to market strategy can change - the effect on R&D Productivity can be seen in big swings, rather than small changes.

Give me a fulcrum, a lever and a place to stand and I will move the earth: Archimedes