Phase transition

The two phase transition mindsets to improve

Two kinds of phase transition problem impact innovation in pharma.

The first, perhaps one of the biggest single killers of innovation: the emphasis on phase transition rates in Development. Groups organised to simply get from phase I to phase II or from phase II to III have a perverse incentive structure. To create a truly agile or innovative organisation would mean breaking that paradigm.

The second is a failure-to-plan that impacts launch. As an analogy, while we can all imagine that the world would be better off with a single design of power socket, the phase between then and now is almost unimaginable (for South Park fans, the ‘underpants gnomes’ problem). There is too much to change. It almost doesn’t matter how much you do your ‘as is’ and ‘to be’, shifting the user base is not going to shift because the gain is less than the hassle. Imagine being forced to change all the sockets in your house, or your business, because someone decided the UK plug was the standard for safety, reliability and more. Pharma misses this challenge when it launches cell and gene therapies, or new classes more broadly - it often presents the ‘to be’ data as compelling enough to change practice, but forgets the practicalities of shifting the user base.

Let’s deal with the second problem first, and the asymmetric learning involved. If I want my gene therapy to succeed in a world in which you, the prescriber, have a perfectly viable enzyme replacement therapy, I need to do more than just provide an equivalent outcome over 4 years at an equivalent cost. This has been true of PCSK9s vs statins, novel heart failure medicines over standards of care, and more. It’s also very true of cell and gene therapies, which on the surface seem magical, but encounter real-world logistics and economic problems. The user experience of the installed base matters - and the user experience is more than simply ‘prescribe and watch’. The day 0 experience (deciding, prescribing, getting it paid for), the day 1 experience (watching for some form of outcome, seeing how the patient is doing), the day 30 experience (is it different in any way?), etc., all matter. How much does the prescriber get paid to do what they did yesterday vs what they’ll get paid now? How much does their comfort with established practice factor in when there’s a totally novel approach to learn? What does the patient experience that they wouldn’t have experienced with the previous gold standard?

Your technology may well be better, on paper. But prescriptions aren’t written on paper - they’re written in the minds of the prescriber, and the better you understand their experience, the more likely you are to launch a successful alternative. Too much time on the data, and not enough on the practicalities, can kill great medicines.

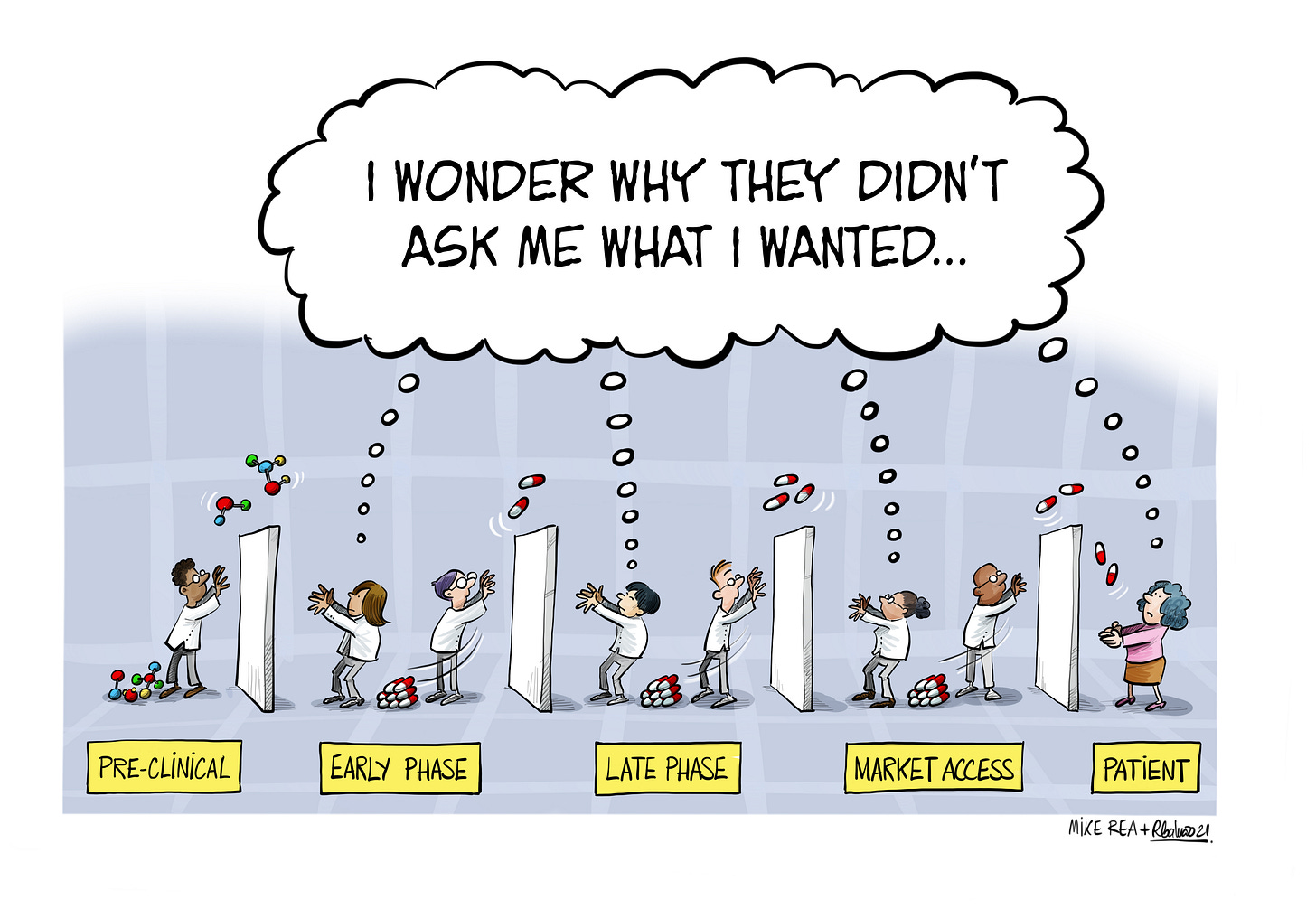

Unfortunately this problem can find its source back in the first problem. Science can win at each phase transition until approval, and then real user experience takes over. A programme that wasn’t designed against that user experience (value endpoints, duration, ease of application, economics and more) will then have an army of sales, medical affairs and more trying to force fit it into a real world application.

Companies will often proudly boast their better-than-average ‘attrition’ rates, despite there being no good way to average out exploratory and confirmatory phases of development. (This is similar to, although not the same as, an approach such as Pfizer’s focus on ‘end-to-end’ rates, which still ignores commercial value.) Not losing drugs at phase I and phase II is not the same as not losing them in phase III, so an average is meaningless. Even an incentive to get drugs to approval is still missing the critical key step that pays for everything that came before. Incentivise groups to produce high phase transition rates and that’s what you get, however poorly that correlates with actual on-market success. These barriers tend to exist invisibly in an organisation, and go unnoticed because no-one questions the idea that drugs fail, for unforeseeable reasons, along the only possible path to the only possible destination (the ‘drug destiny is foretold’ approach). Of course, that approach doesn’t withstand any scrutiny.

Many companies that think of themselves as ‘learning organisations’ miss this problem, preferring their learning to be linear. Presented with a more innovation-focused optionality approach like FIVE-X, we have heard ‘we agree it would be better, but it would break our incentive structure’. The irony of this, for me, is that asymmetric learning itself has its own phase transition challenge - shifting pharma from its traditional approach is more than a ‘better approach’ problem. The stage between the the system everyone grew up with and a better one is a hard one for companies to imagine.

Data that are easy to collect may be at odds with, or insufficient for, evidence that will effect a phase transition in the market. Ironically, data that are easy to collect continue to drive the phase transition rate problem in more established pharma companies - for as long as it’s easy, and you get paid often enough, it’s hard to shift to a more productive system.