The obvious vs the obverse

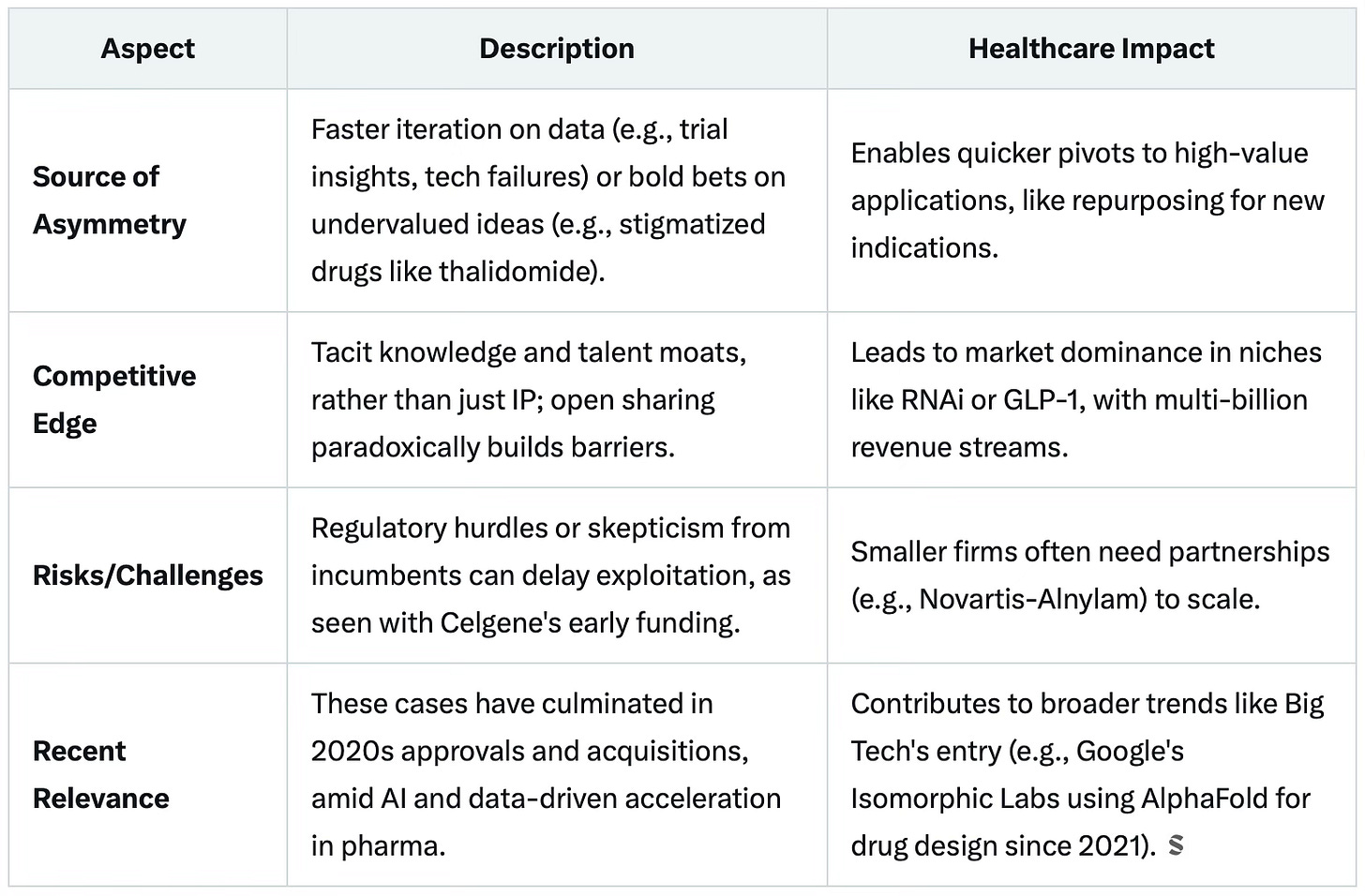

I tend to think that Asymmetric Learning is self-explanatory - it would be more odd if learning was symmetric, or synchronous, at every company at the same time. The idea that advantage can be gained from how, and how fast, a company learns seems intuitive to me, but I’ll accept that the term is hardly widespread yet (whereas remarkably nonsensical ideas like the TPP or eNPV are ubiquitous).

Asymmetric learning refers to situations where one entity acquires knowledge, insights, or capabilities at a faster rate or deeper level than rivals, enabling it to capitalise on opportunities ahead of the competition.

This can stem from innovative approaches, early adoption of emerging technologies, or superior internal processes for experimentation and adaptation. We’ll come later to the question of how the M&A trend increases the need for this essential skill.

Here are recent examples from the industry, to illustrate how companies gained an edge through faster learning cycles, often involving AI, data-driven strategies, or bold pivots based on proprietary insights.

1. Novo Nordisk's Exploitation of GLP-1 Agonists for Weight Loss

Novo Nordisk developed semaglutide initially as a treatment for type 2 diabetes (branded as Ozempic, approved in 2017). Through clinical trials and real-world data analysis, the company quickly learned about its significant weight-loss side effects - insights that were not immediately apparent or prioritized by competitors. This asymmetric learning allowed Novo to repurpose the drug as Wegovy for obesity, gaining FDA approval in 2021 and rapidly scaling production (maybe some more attention could have been paid here, though!) and marketing.

By 2023, Wegovy had captured a dominant market share in the booming anti-obesity drug space, generating billions in revenue before rivals like Eli Lilly fully ramped up their competing product (tirzepatide, branded as Mounjaro/Zepbound). Novo's early pivot was based on internal trial data interpretation and patient feedback loops, outpacing the industry's slower recognition of GLP-1's broader potential. This led to a market valuation surge for Novo, making it Europe's most valuable company by 2023.

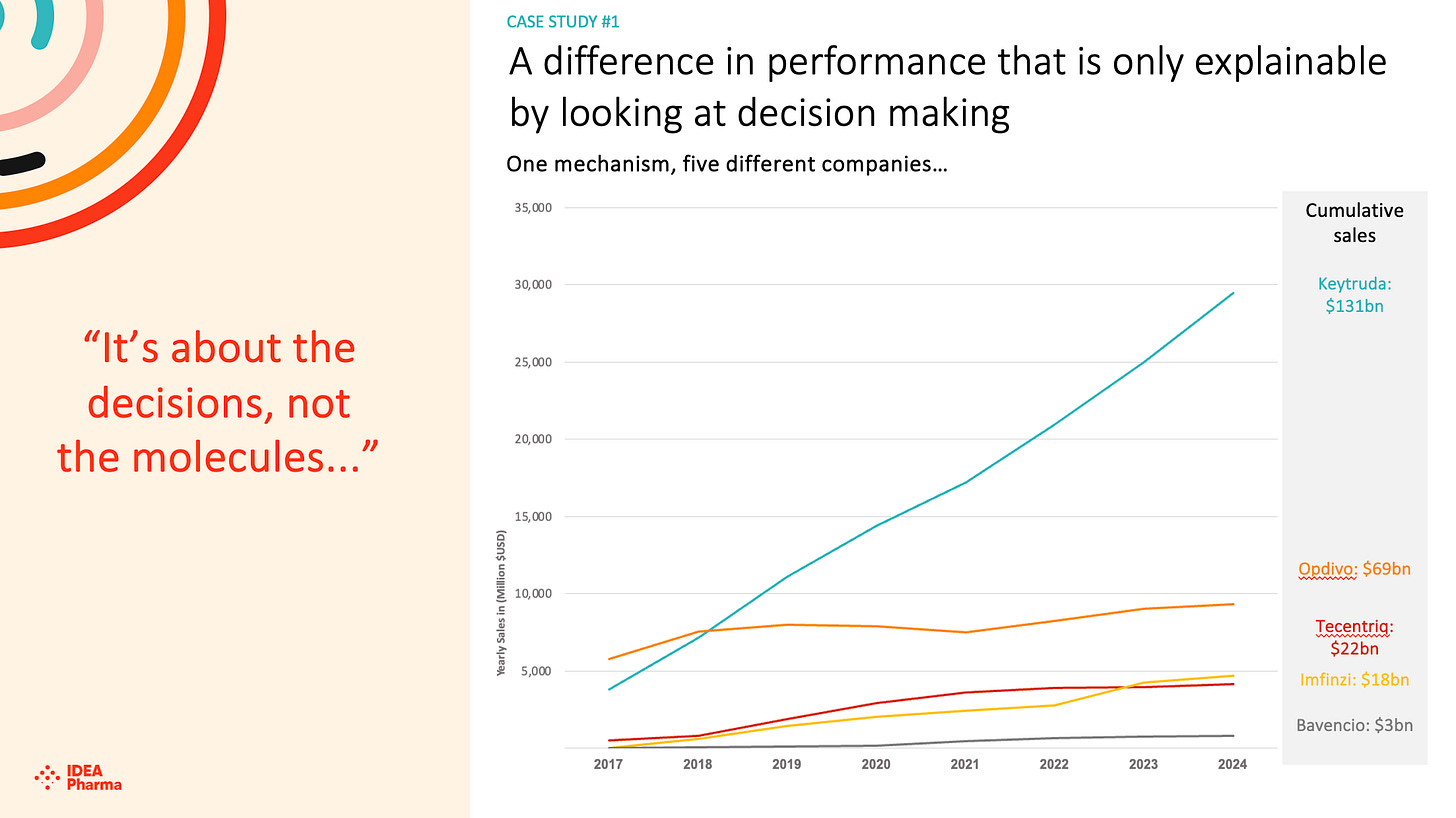

As could be argued in the Opdivo/ Keytruda case, however, it is possible that early leadership tends to a classical behavioural psychology challenge - risk aversion, or risk aversion in the domain of gains, a key component of prospect theory developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. When individuals perceive themselves as being in a position of gain (such as an early win or lead - both Opdivo and Ozempic/ Wegovy ‘won’ launch), they tend to become risk-averse, preferring to secure and protect their current advantage rather than pursuing additional risky opportunities that could yield greater rewards but also carry the potential for loss. This stems from the value function in prospect theory being concave for gains, meaning people or companies experience diminishing sensitivity to further increases and prioritize certainty to avoid any regression from their reference point of success. The addition of new indications sounds attractive in retrospect, but choosing to put a winning drug into a trial that risked negative, or lower than expected, outcomes clearly inhibited both BMS and Novo Nordisk.

This contrasts with behavior in the domain of losses, where people often become risk-seeking to try to recover. A related sub-concept within prospect theory is the certainty effect, which further explains why people overweight certain outcomes (like locking in an existing win) over probable ones (like gambling for more), even if the expected value of the riskier option is higher. For example, someone (or someone’s Board of Directors) might choose a guaranteed smaller additional gain over a chance at a larger one to safeguard their position.

2. Celgene's Development of Thalidomide Derivatives for Cancer

Oncologist Dr. Angus Dalgleish rediscovered thalidomide's efficacy for severe autoimmune conditions in the late 1990s/ early 2000s, but faced establishment resistance due to its historical birth-defect risks.

Celgene, a small biotech with just 12 employees at the time, learned from Dalgleish's insights and funded his lab when major institutions (e.g., MRC, CRUK) refused. This asymmetric bet - ignoring conventional wisdom and exploiting overlooked repurposing potential - led to the development of lenalidomide (Revlimid) and pomalidomide, now standard treatments for multiple myeloma and lymphoma. By the 2020s, these drugs generate ~$10 billion annually for Bristol Myers Squibb (which acquired Celgene in 2019). Competitors were slower to explore thalidomide analogs due to stigma, giving Celgene a multi-year head start in immunomodulatory drugs.

3. Alnylam's Sustained Leadership in RNAi Therapeutics

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals has exemplified asymmetric learning through its persistent focus on RNA interference (RNAi) technology, a field it pioneered in the early 2000s. While many competitors abandoned RNAi after early setbacks (e.g., delivery challenges), Alnylam iterated rapidly on lipid nanoparticle delivery systems and clinical data, learning from failures to refine its platform. (My interview with John Maraganore discusses this mindset in some detail.) This paid off in the 2020s with approvals like Amvuttra (2022) for hereditary ATTR amyloidosis and ongoing expansions into cardiovascular and CNS diseases. By 2024, Alnylam reached a $20+ billion valuation (recent increases have taken this up to around $60bn), largely without relying on mergers or acquisitions - unlike diversified pharmas like Amgen or Gilead. Novartis' early $60 million bet on Alnylam in the 2000s (when RNAi was unproven) also reflects this, as Novartis acted ahead of peers by partnering aggressively, gaining access to tech that fueled its own pipeline.

4. Genentech's Tacit Knowledge Moat in Recombinant Proteins and Beyond

Genentech (now part of Roche) built an enduring advantage through open publication and talent attraction starting in the 1970s-1980s, but its asymmetric learning model continues to yield results in the 2020s. By openly sharing recombinant DNA methods (e.g., cloning human insulin in 1978 and publishing details immediately), Genentech created a market for biotech while accumulating tacit knowledge - non-codifiable expertise in processes like protein expression - that competitors couldn't easily replicate. This flywheel attracted top talent, enabling pivots into monoclonal antibodies and now AI-integrated platforms (e.g., under Aviv Regev's leadership since 2020). In the 2020s, this has positioned Genentech ahead in oncology and autoimmune therapies, with drugs like Tecentriq generating billions (let’s accept, of course, that they were late to the PD1/ PDL1 party).

Rivals like Pfizer or Merck have relied more on acquisitions to catch up, highlighting Genentech's learning edge.

These examples show that asymmetric learning often thrives in innovative, data-rich environments like biotech, where one company's superior learning loop can create lasting advantages. However, as seen in cases like Chinese firms outpacing U.S. counterparts in cancer therapies, global competition can erode leads if not defended aggressively.

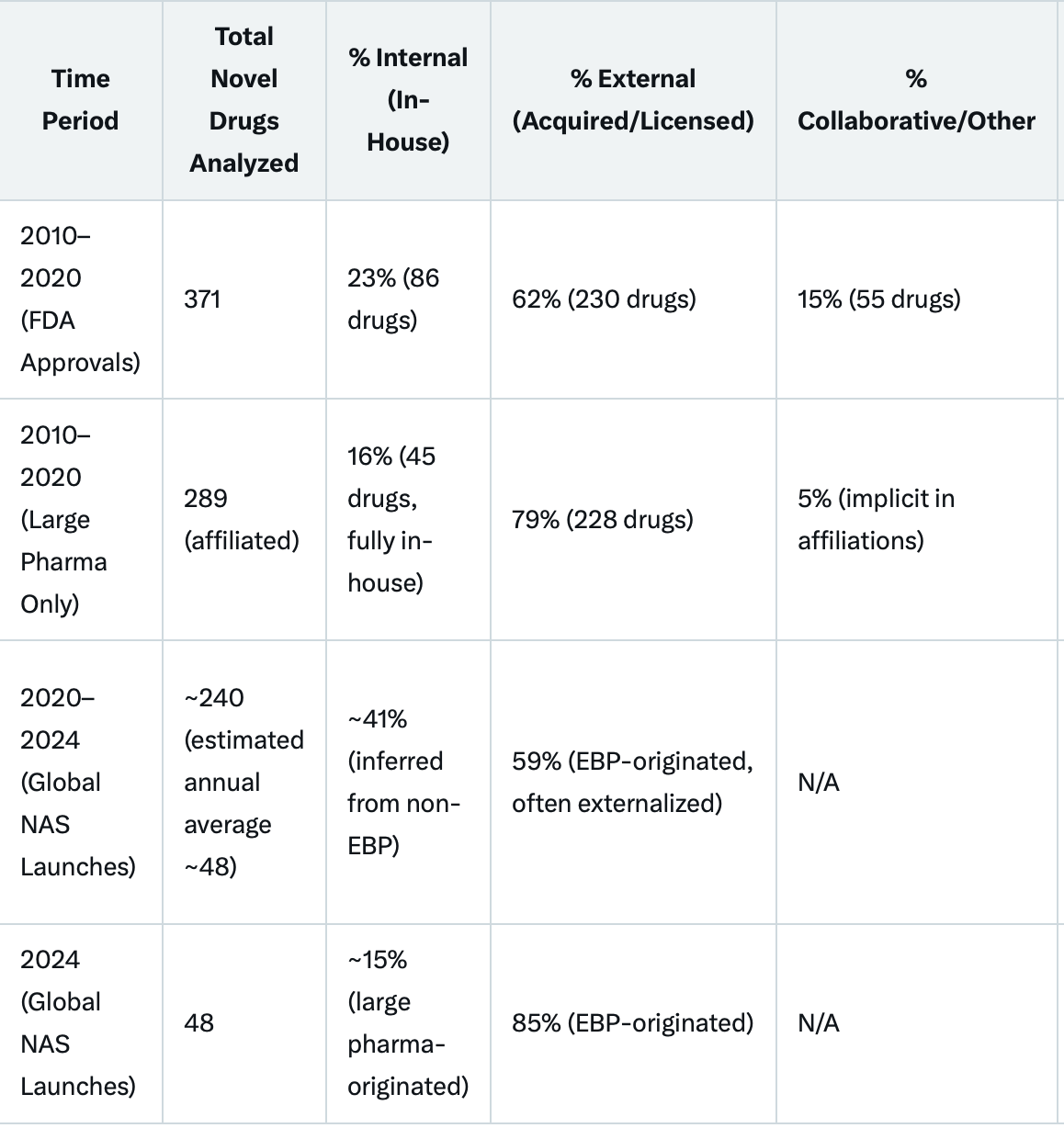

The question of how much ‘innovation’ in pharma now comes from acquisition/ licensing vs internal Discovery came up in a seminar we did with one of the industry’s largest companies this week. While it ‘feels’ that way, I searched for numbers:

Key Trends and Proportions

Overall Industry Externalisation (2010–2020): An analysis of 371 FDA-approved novel drugs found that 62% (230 drugs) underwent at least one ownership transfer via licensing, joint ventures, or mergers and acquisitions (M&A) during their lifecycle, compared to only 23% (86 drugs) that remained fully internal from origination to commercialization (the remaining 15%, or 55 drugs, involved collaborations without full ownership transfer). This externalization often occurred during development (52% of drugs were externally sourced at this stage) or commercialization (62%), with early-stage (pre-clinical) work more likely to be internal (68%). Peripheral institutions like small- and mid-cap biopharma firms or public research bodies originated most treatments, highlighting a "fragmented innovation nexus" where big pharma relies heavily on external inputs. (I’d continue to wonder why so many companies like their pre-clinical to be internal…)

Origination by Emerging Biopharma (2020–2024): Of novel active substance (NAS) launches globally, 59% originated from EBPs (small companies with <$500 million in annual revenue or <$200 million in R&D spend), up from 53% in 2015–2019. In 2024 specifically, 85% (41 out of 48) NAS launches originated from EBPs, compared to just 15% from established large pharma. These EBP-originated drugs frequently reach market through partnerships, licensing, or acquisitions by bigger firms, indicating that even when large pharma commercializes a "success," the core discovery is often external.

Large Pharma's Internal vs. External Reliance (2010–2020): Large biopharma companies (e.g., those with >$50 billion market cap) were affiliated with 77% (289) of the 371 FDA approvals but fully developed only 12% (45 drugs) in-house. The remaining 61% (228 drugs) involved external sourcing, with 55% of these acquired or licensed during development and 31% at commercialization. This suggests that for big pharma, internal discovery accounts for a minority of successes, with external strategies driving the majority.

M&A Activity and Its Role: From 2010–2023, there were 3,006 pharma M&As, increasingly targeting early-stage assets (e.g., preclinical drugs rose from 10% of targets in 2010–2021 to 18% in 2022–2023). About 11% of a dataset of 31,837 drugs were involved in M&As from 2018–2023, with oncology (25% of deals) and biologics seeing heavy activity. Each M&A deal correlates with ~0.53 additional FDA approvals (2012–2021 data), underscoring its role in bolstering pipelines.

In many ways, external radars are a valuable asymmetry - the ability to see the value in early stage assets is clearly widened if you look at the whole landscape, instead of inside your own labs. It also introduces asymmetries in companies’ ability to partner, and work with partners.

While internal discovery remains vital for some breakthroughs (e.g., in established therapeutic areas), the data substantiates that 60–85% of recent successes involve external elements, enabling faster innovation amid rising R&D challenges. This external focus has risks, such as higher drug shortage odds post-M&A (24.3% increase), but it has sustained approval rates (e.g., ~50 novel drugs/year).

The title: I wanted to contrast something clear and apparent (the obvious) with its counterpart, flip side, or less visible aspect (the obverse)…