I’ve written a lot about the Target Product Profile, because it is a singularly corrupting element in early phase.

The TPP kills innovation in pharma. 'The TPP' is set up to fail, because it is the product of a failed/ failing process.

It is a stubbornly resistant enemy, however. Despite its relatively recent entrance to pharma, a mini industry has emerged around its creation, testing and more. Even though it doesn't withstand scrutiny, once it is there, it is hard to shift, like any anchor.

Development should be focused on at least three goals: is it approvable, is it likely to get to market, and will the market want and pay for it? Each is necessary but insufficient.

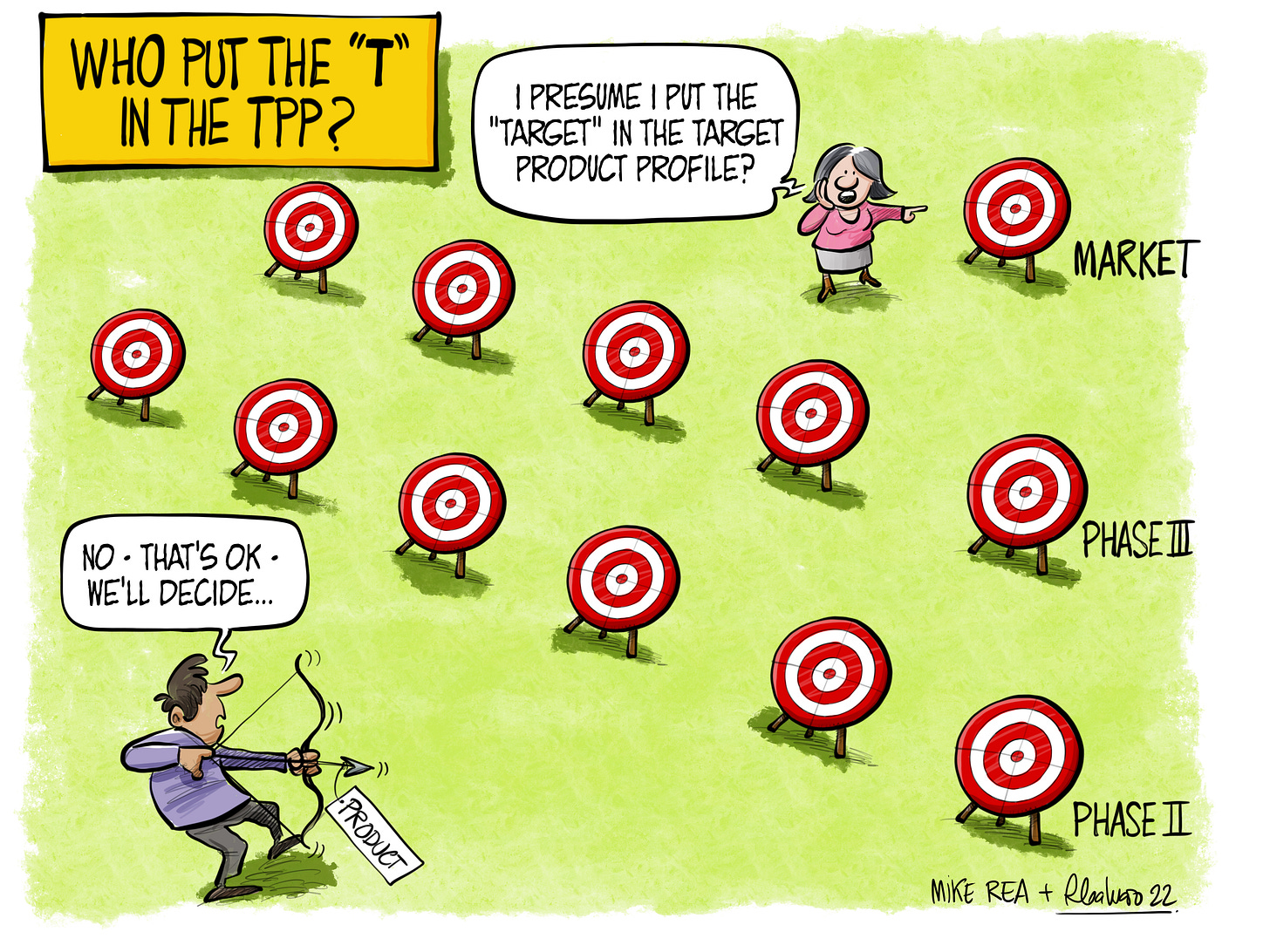

Whatever the fundamental problems of the TPP (see the links below for more), the single biggest reason that it fails its intended task is that it is rarely a target - more often it is a projected profile, an expected profile based on an already-decided path to market, rather than a validated target opportunity profile. Were it to be a target profile, one might expect that profile to have been provided by those who understand the commercial opportunity best - that is the ultimate target, surely?

Shooting short of a commercial target may well suit internal incentives, but the problem that we see in many pharma companies can be traced to this: return on invention, or the creation of value from pipeline, is the very definition of innovation, yet many companies’ launches are underwhelming.

It can be argued back that Commercial do get an input, but let’s consider why that is insufficient: that input is bounded by a TPP. ‘TPP testing’ or forecasting start with that document. They should start with a range of very different profiles, but the anchoring effect of the starting document remains pervasive.

I’m slightly ashamed to say that I do still watch The Apprentice, and remain fascinated by their ‘market research’ phase. Essentially, it goes like this: here’s this terrible thing we developed, please tell us what you think. And then, the terrible thing is not redeveloped, even if the sales pitch might be influenced. It seems odd, but that is exactly what happens in pharma every day.

The key benefit of our Asymmetric Learning approach is that the three legs of the stool (Achievable, Approvable, Commercial) are integrated as part of the design process - the exercise is collaborative and iterative. Thinking outside of the TPP box starts by seeing it as a box, as a sealed package from one department. Agreeing on its contents should be a whole company exercise.

For reference, these pieces, on the fundamental logic problem of the TPP process: Spherically senseless

The End Of The TPP/ The Beginning of the Draft Label

or this article, on the reasons it should not be part of strategic planning: TPP: The Perennial Problem.

To drive the TPP forward, and make it more useful for innovation processes, this piece, on how, if you correctly see a TPP as a prototype, you should be doing a lot more: How many TPPs? How about 1000?

You may prefer a video: The Target Product Profile - an enemy of innovation