In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical R&D, where nine out of ten drug candidates ‘fail’* and timelines can stretch into decades, the pressure to deliver is relentless. Yet, too many teams cling to a comforting illusion: steady, linear progress. Step by step, data point by data point, they’ll inch toward the finish line. It’s a model that feels safe, measurable, and oh-so-scientific. But as one insightful observer put it recently on X, in reply to my post: “Spot on. Linear learning just doesn’t cut it in high-stakes R&D. Reminds me of Jared Noble’s point that markets reward those who find those non-obvious edges. It’s all about the big, uneven leaps.” This isn’t just a quip - it’s a wake-up call. Drawing from the world of stock trading, where survival demands spotting hidden advantages amid chaos, the analogy hits home for pharma innovators.

Let’s unpack why ditching the linear path could be the edge your pipeline needs - and why I was intrigued to find out more about Jared Noble. Clearly ‘linear learning’ sits in opposition to asymmetric learning, but I hope you’ll forgive me attacking the other team…

The Trap of Linear Learning

Imagine R&D as a conveyor belt: hypothesis, experiment, iterate, repeat. It’s the backbone of good science - controlled variables, reproducible results, incremental refinements. In theory, it builds a tower of evidence, brick by predictable brick. But in practice? It crumbles under the weight of complexity. Pharma isn’t assembling IKEA furniture; it’s navigating a labyrinth of biological unknowns, regulatory mazes, and market whims. Linear approaches assume a straight-line trajectory from lab bench to blockbuster, ignoring the 90% attrition rate that turns most paths into dead ends. The result? Stagnation. Teams burn cycles on low-hanging fruit, optimizing what’s already known rather than venturing into the fog of the unknown. Resources dwindle, morale dips, and breakthroughs? They remain elusive, hoarded by those willing to zig when everyone else zags.

Lessons from the Trading Floor: Non-Obvious Edges Win

So, we come to Jared Noble, a stock strategist whose X feed (@Jared_Noble) seems to be a goldmine for anyone chasing alpha in volatile markets. Noble’s trades - think 55-116% gains on names like $TSLA and WLDS 0.00%↑ - aren’t born from textbook plays. They’re the fruit of “non-obvious edges”: subtle, unconventional insights that evade the herd. In trading, an edge is your repeatable advantage - be it a proprietary algorithm, contrarian sentiment read, or pattern hidden in plain sight. Obvious ones? They vanish fast, arbitraged away by algorithms and copycats. The real rewards flow to the non-obvious: the fleeting inefficiency you spot before Bloomberg headlines it.

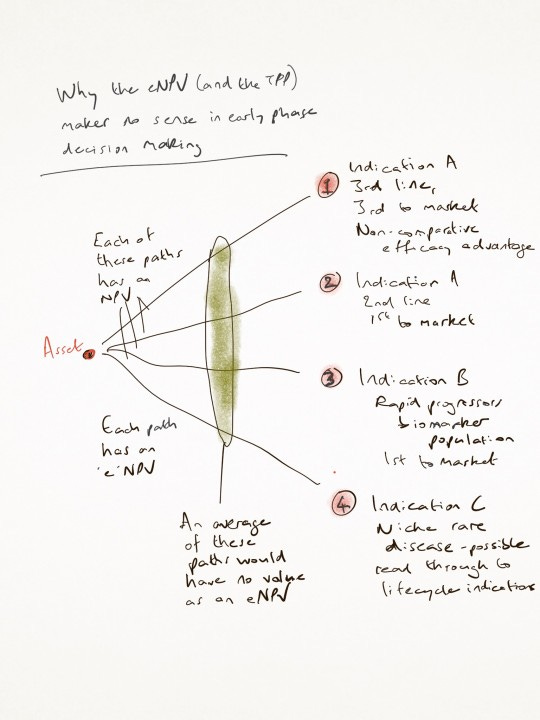

Markets are brutal meritocracies. They don’t care about pedigree or persistence; they reward asymmetry - bets with capped downside and uncapped upside. Noble’s playbook echoes this: scan widely, act decisively on the leap that feels counterintuitive, and let the uneven ride compound your wins. Does that sound familiar? Pharma R&D is its own zero-sum game. With billions at stake and competitors nipping at your heels, the “efficient market” of drug discovery quickly commoditizes the obvious. Everyone’s running Phase I trials on the same targets. But the winners? They unearth the non-obvious - the rare disease pivot, the repurposed compound, or the AI-driven hypothesis that rewires biology.

Translating Edges to the Lab: Big Leaps in Pharma

So, how do we import this mindset into drug development? It’s not about abandoning rigor; it’s about amplifying it with asymmetry.

Cultivate Curiosity Over Checklists: Linear learning loves protocols. Non-linear thrives on questions without answers. Encourage “edge hunts” - dedicated sprints where teams explore wild-card ideas, like cross-pollinating oncology insights with neurology data. Remember mRNA’s leap from vaccines to cancer therapies? That wasn’t linear; it was a Noble-esque bet on an overlooked edge.

Embrace Uneven Timelines: Big leaps aren’t tidy. They demand tolerance for “productive failure” - the 80% of experiments that seem to flop spectacularly but illuminate the path. Tools like adaptive trial designs or real-world evidence can compress these leaps, turning months of drudgery into weeks of revelation.

Build Asymmetric Teams: Markets reward diverse edges; so should your R&D teams. Blend PhDs with traders, artists with clinicians. Noble’s chart-reading wizardry stems from seeing patterns others miss - import that to pharma by hiring for orthogonal thinking. What if your next lead compound came from a bioinformatician moonlighting as a poker pro?

Real-world proof? Look at CRISPR’s gene-editing revolution. It wasn’t a straight shot from bench to bedside; it was a series of jagged pivots, fueled by non-obvious connections between bacterial immunity and human disease. Or consider the rapid warp-speed of COVID vaccines: linear would’ve taken years; the leap mindset delivered in months. (The link is to my STAT article, back in 2021… Key Covid time…)

The Payoff: Rewarding the Leapers

In Noble’s world, edges compound into fortunes. In pharma, they compound into ‘cures’ - and market dominance. But here’s the challenge: these leaps require courage. Leadership must shield explorers from the linear accountants who demand quarterly KPIs. Investors must fund the fog, not just the finish line. The alternative? An industry stuck in neutral, watching agile biotechs lap the field. So, pharma pioneers: Audit your pipeline. Where are you grinding linearly when a leap beckons? Hunt those non-obvious edges. Embrace the uneven. The markets - biological and financial - will reward you handsomely.

*When I asked Grok to summarise my views on ‘failure’ in pharma, it gave me this:

Mike Rea, October 30, 2022, reply to a popular visualization of drug development attrition. It challenges the binary framing of success and failure in early clinical phases (Phase I/II), arguing that it distorts decision-making and learning. This post resonates deeply because it reframes failure not as an endpoint but as a flawed metric that ignores absolute numbers of dropouts versus relative rates— a common pitfall in R&D that leads to inefficient resource allocation.

Here’s the post in full:

The words ‘failure’ and ‘success’ are the wrong construct for pI/pII, because you get this…

(Quoting Alex Telford’s Sankey diagram showing that while Phase II has the highest rate of failure, Phase I accounts for the most absolute drug dropouts out of 100 entering clinical development, with only ~8 reaching approval overall.) This insight highlights how overemphasizing “success rates” in early phases can mislead teams into chasing illusory progress, rather than using data for broader learning. It sparked discussion on metrics like PTRS (Probability of Technical and Regulatory Success). In a field where ~90% of candidates fail, Rea’s point underscores the need for asymmetric, learning-focused approaches over rigid go/no-go binaries. For context, Rea often ties this to his broader critiques of pharma’s “Predict, Pick, Plan” model, which amplifies such failures by prioritizing premature predictions over adaptive exploration.