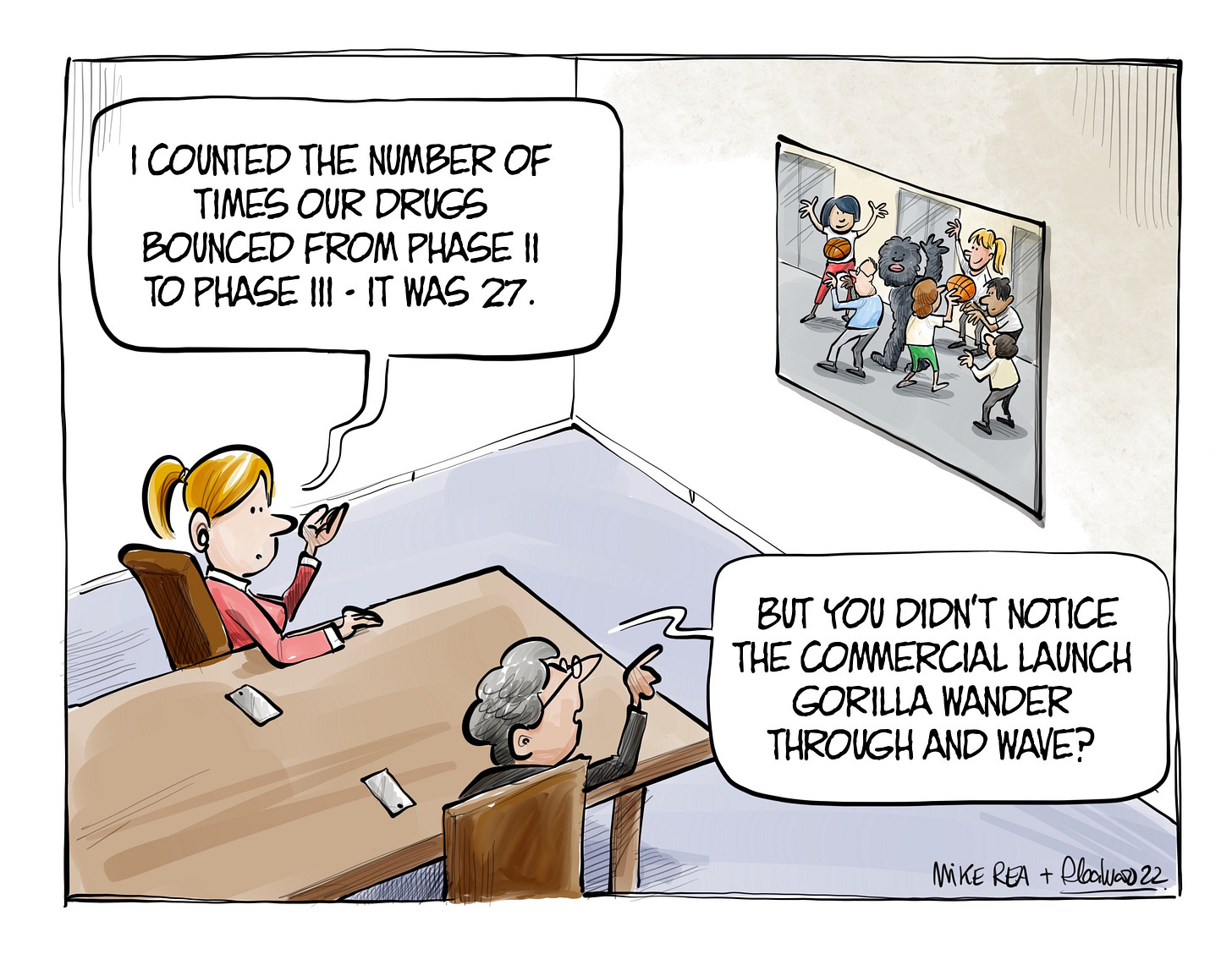

Selective Inattention

Missing the gorilla, focussing on the bounces

Since writing my piece ‘Who Puts The T in the TPP?’ I have had a lot of conversations with people who both agree that they should know, and that it is a lot fuzzier than it should be in their organisations.

When Deloitte looked at launch performance recently, they said

We analyzed actual and forecast sales for novel drugs approved in the USA between 2012 and 2017, and found wide variability in launch performance. In their first year, 36% of all drugs failed to meet market expectations.

Most new drugs continue with the revenue trajectory set at launch. About 70% of products that miss expectations at launch continue doing so in subsequent years, and around 80 percent of products that meet or beat expectations continue to do so afterward

Drugs launched by large companies underperform compared to their counterparts

Note that they’re talking about performance against analyst expectation/ forecast, not company forecast. So many of the papers on this subject tend to look at averages, which of course ignores the asymmetry that we see in both inputs and outputs. (It is also a terrible way to look at this question - there is no average drug, and no two companies add value to their pipelines in the same way.) Traditionally, we have seen only 1 in 4 launched drugs return their own investment. There are no signs that number is improving.

However, this does not stop companies focusing on attrition rates as a measure of productivity. Or, to focus on clinical trial ‘success rates’. Unsurprisingly, McK don’t quite get it, leaning into the averages heavily. More typically, there is an assumption that approvals are a good enough surrogate. That is, if the 1 in 4 is just an extra layer of ‘attrition’ it spreads across the companies, so no-one is penalised. That, as we see in the Deloitte paper, is not true.

Any measure of productivity that ignores the need for a launched drug to get to patients is a meaningless surrogate metric. To get to patients requires the things you’d expect: approval certainly, but also market access (odd how pharma is about the only industry that talks about this as a separate step), physician preference, payer preference and patients willing to take and keep taking it. That is, the Target in the TPP should be based on a drug that has a chance of market success. Anything else is just expensive, unproductive R&D. Science may well have been followed, but it stopped short of meeting real people’s needs.

(If you’re too young to know the context for my cartoon, you might like the original Selective Attention video…)

The phase transition problem remains baked into the incentives in most major pharma companies, and into the papers on R&D productivity. It does complicate things somewhat, but unless we launch drugs that return their investment, all of the investment is at risk.

What if pharma teams would be incentivised to apply a different, asymmetric learning approach to create value for patients, prescribers, payers and return on invention vs being incentivised for getting an asset from one phase to the next...

Possible Punchline: "All they <told> us to do, was to count the bounces!"